I don’t know about you, but I am still feeling rather sad about the untimely passing of Dr. McDougall. I guess I had been counting on him being around for another couple of decades. Before his passing, I’d seen only a couple interviews and had never read his books. So it felt appropriate and consoling to get hold of a copy of The Starch Solution (published in 2012) to learn more about his journey to whole food, plant-based (WFPB) living and understand his particular views on health and disease. I greatly loved the book and found it hard to put down. As its title suggests, however, this article is not about Dr. McDougall; rather, it’s about the person he credits in The Starch Solution with introducing him to the importance of fiber—Dr. Denis Burkitt.

On learning of Burkitt’s influence on McDougall, I was surprised his name wasn’t familiar to me and could not resist the temptation to go down the nutrition history rabbit role to learn more. Cross-referencing The Future of Nutrition, I realized Dr. Campbell had included Burkitt in his overview of the pioneering doctors who hypothesized a connection between cancer (in Burkitt’s case, colon cancer) and nutrition. Digging around online, I discovered a 2018 academic review of his work, “Denis Burkitt and the origins of the dietary fibre hypothesis.”[1] This paper provides an in-depth analysis of Burkitt’s role in the radical (at the time) dietary fiber hypothesis and the roles of several other characters important to that story. Following is a summary of what I learned and my thoughts on Burkitt related to wholism and that proverbial elephant.

Source: SantMat, “Elephant and the Blind Men” (2018)[2]

If you are unfamiliar, Dr. Campbell’s adaptation of the Blind Men and the Elephant parable to our disease care system is a metaphor he uses in the book Whole. In the story, six blind men feel their way around different parts of a single elephant: leg, tusk, trunk, tail, ear, and belly. Trying to describe what an elephant is, they each have a different idea. One believes it is like a tree trunk; another, a snake; etc. This is a reductionist view of an elephant. While each is partly correct, none of them know what the whole elephant is or can do. Similarly, a reductionist view of disease leads us to treat an array of different symptoms with different medications and surgeries rather than addressing the single root cause of the symptoms.

Dr. Denis Burkitt (1911–1993) grew up in Northern Ireland, studied medicine at Trinity College, Dublin, and took his medical board exams in Edinburgh, Scotland. Devoutly religious, he felt called to enter the British colonial medical service in order to do “God’s work,” which for him meant bringing Western medicine to Africa. He moved his young family to Kampala, Uganda, where he worked as a surgeon for 20 years following the Second World War. Viewing him from a contemporary perspective on colonialism, we might reflexively disapprove of his association with the British Empire. Nonetheless, his experience as a surgeon in Africa was essential to his contributions to medical science and his becoming an early advocate for preventive medicine.

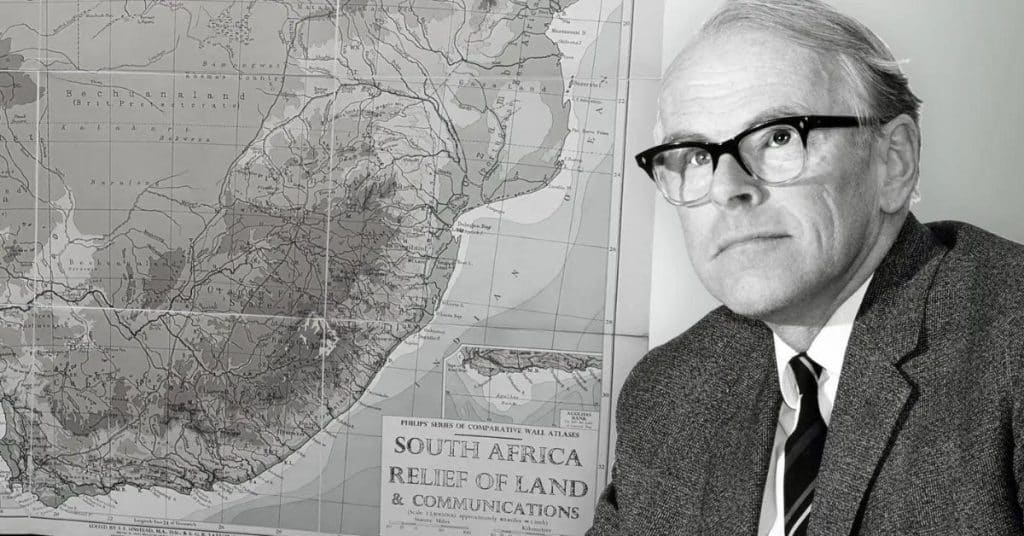

Denis Burkitt in Africa, circa 1970. Wellcome Images L0040757. Accessed from John H. Cummings and Amanda Engineer[1]CC BY

Burkitt’s first claim to medical research stardom is for having determined the cause of a deadly lymphoma, primarily of the jaw, that occurred in young children in Uganda. Carefully studying the tumor’s geographic distribution, he determined that the tumor was due to a virus that flourished only under certain conditions of altitude, temperature, and rainfall. He also showed that the lymphoma could be treated with relatively low doses of existing chemotherapeutic agents, thus healing many sick children. The lymphoma was named after him and is still known as Burkitt Lymphoma. Because of this major contribution to medical science, he was able to obtain research funding when he returned to the UK in 1966 and decided to turn his attention to understanding the causes of colon cancer.

Back then, fiber wasn’t even listed in food tables. It was generally considered inert roughage of no great importance. As the 2018 review notes, “The word ‘fibre’ did not appear in the index of the main textbooks of nutrition and gastroenterology nor was there a listing for it in the Cumulated Index Medicus, the bible for researchers before the digital age. There was no book on the subject or articles in any of the leading medical journals.” However, views of fiber were changing, and because Burkitt had relationships in Africa and traveled widely to lecture about his eponymous lymphoma, he could meet other doctors and researchers whose work was relevant to getting to the root cause of bowel cancer. As a result, he functioned as a sort of intellectual hub, bringing together many disparate sources of information to inform his hypotheses and experiments.

As the 2018 review notes, Burkitt and most of the people who influenced his thinking “at no time would have called themselves scientists, had worked mostly in Africa, largely eschewed technology and commended simple observations and experiments.” And yet, because of their colonial experience, these doctors had something that their Western-based contemporaries lacked: a wide-angle view of the geographic distribution of disease. They had to be generalists overseeing large territories rather than specialists in one particular field of medicine. Collectively, they had a view across Africa, India, and Western nations. Importantly, they realized that if a group of diseases occur together in the same population or individual, the diseases likely share a common cause (a concept first articulated by Surgeon Captain Peter Cleave). This concept seems to be regaining attention today (e.g., the use of the term metabolic syndrome to describe a cluster of conditions that occur together, increasing the risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.)

I will highlight three of Burkitt’s sources and collaborators among several important figures covered in detail in the 2018 paper.

By 1971, Burkitt was ready to bring all the puzzle pieces together. He marshaled the existing epidemiological evidence along with data he had collected from over 1,400 rural hospitals in Africa and India, with whom he had established what today we would refer to as data-sharing agreements. (For a fee, these hospitals provided him with disease incidence data every month.) He formulated a hypothesis to explain the epidemiological evidence, namely that dietary fiber deficiency caused increased transit time, uneven intraluminal pressures, and unfavorable changes in the microflora, which he proposed led to the degradation of bile acids into carcinogenic byproducts. He then tested his ideas experimentally and published a landmark paper that quickly became a citation classic.[3]

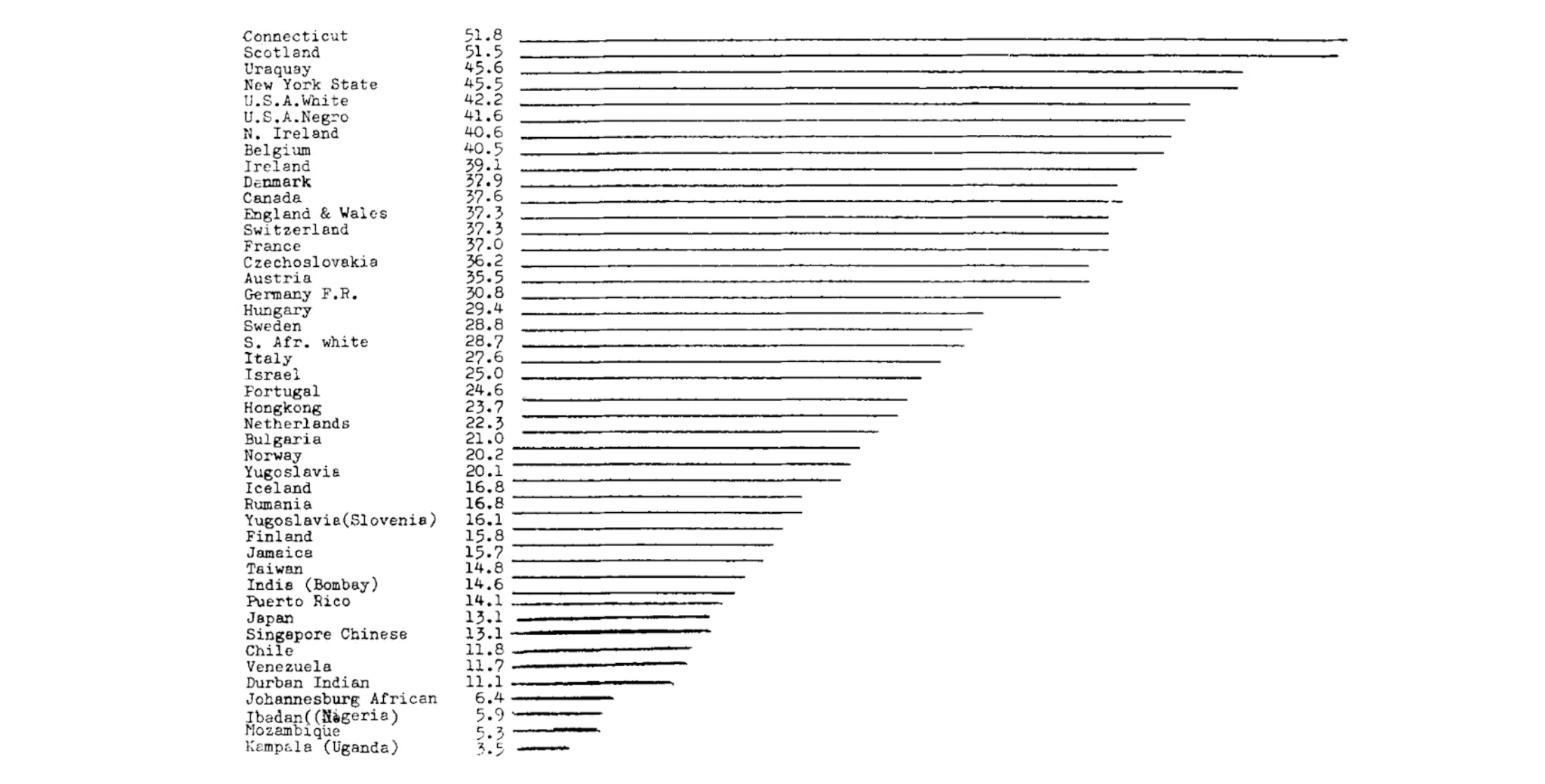

According to the authors of the 2018 review, “While [Burkitt’s 1971] paper contains no statistics or P values, it is outstanding for a number of reasons, not least of which is that Burkitt derives from the epidemiology ideas which he then tests experimentally, suggests a mechanism and then comes up with a solution for prevention.”[1] It is a highly readable paper with some very compelling charts, reproduced below.

(A) Epidemiological evidence (Note the massive difference between the incidence of colon cancer in Western populations, including Blacks in the US (“U.S.A Negro”), South African whites, and black populations in Johannesburg, Nigeria, Mozambique, and Uganda.)

Age-standardized incidence rates for cancer of the colon and rectum in men 35–64 years of age[3] Modified from Doll, “The geographic distribution of cancer” (1969): Denis P. Burkitt, Epidemiology of cancer of the colon and rectum (1971)

(B) Burkitt Experiment 1—Effect of Diet on Intestinal Transit Time (Note that the students in the African boarding school had a diet that Burkitt described as semi-European.)

Source: Denis P. Burkitt, Epidemiology of cancer of the colon and rectum (1971)[3]

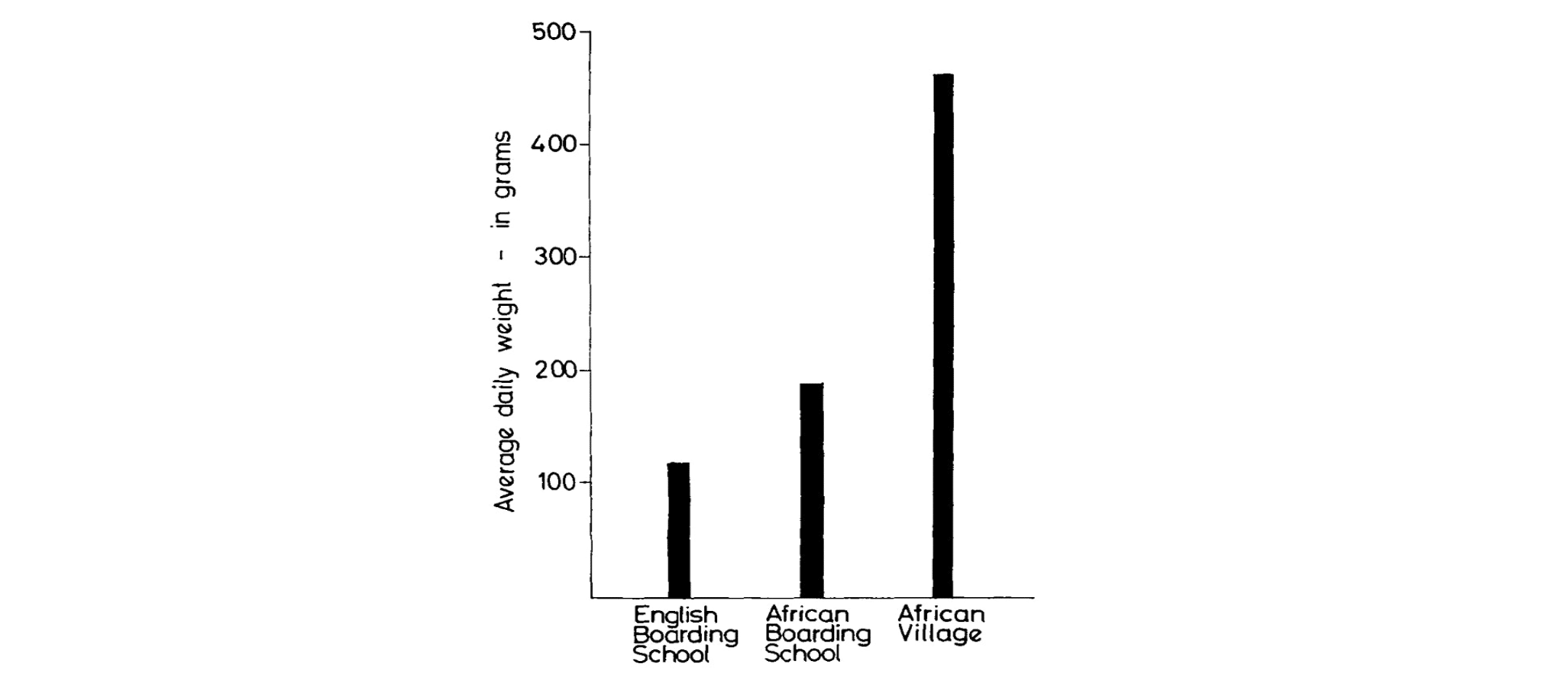

(C) Burkitt Experiment 2—Effect of Diet on Stool Weight (As above, the students in the African boarding school had a diet that Burkitt described as semi-European.)

Source: Denis P. Burkitt, Epidemiology of cancer of the colon and rectum (1971)[3]

(D) Schematic hypothesizing the relationship between diet and bowel cancer

Diagrammatic representation of possible relationship between diet and cancer of the bowelSource: Denis P. Burkitt, Epidemiology of cancer of the colon and rectum (1971)[3]

In concert with the same group of doctors and researchers, Burkitt extended his fiber theory based on the geographic distribution of a wide range of “non-infective diseases,” including coronary heart disease, obesity, and diabetes. Over time, he came to believe that a low-fiber diet increased the risk of these diseases in addition to colon cancer. As the 2018 review asserts, in the 1970s, “Simply grouping these diseases together as having a common cause was groundbreaking.” His 1982 paper, published in the South African Medical Journal, explained that many Western diseases, including “coronary heart disease, diabetes type II, gallstones, diverticular disease of the colon, appendicitis, hiatus hernia, colorectal cancer, varicose veins, hemorrhoids, venous thrombosis, obesity and hypertension,” scarcely existed in developing countries, and he attributed these differences to profound differences in diet.[4] In this regard, and how he combined epidemiological evidence with experimental studies, his work foreshadowed Dr. Campbell’s more comprehensive and rigorously designed investigations into the relationship between diet, health, and disease.

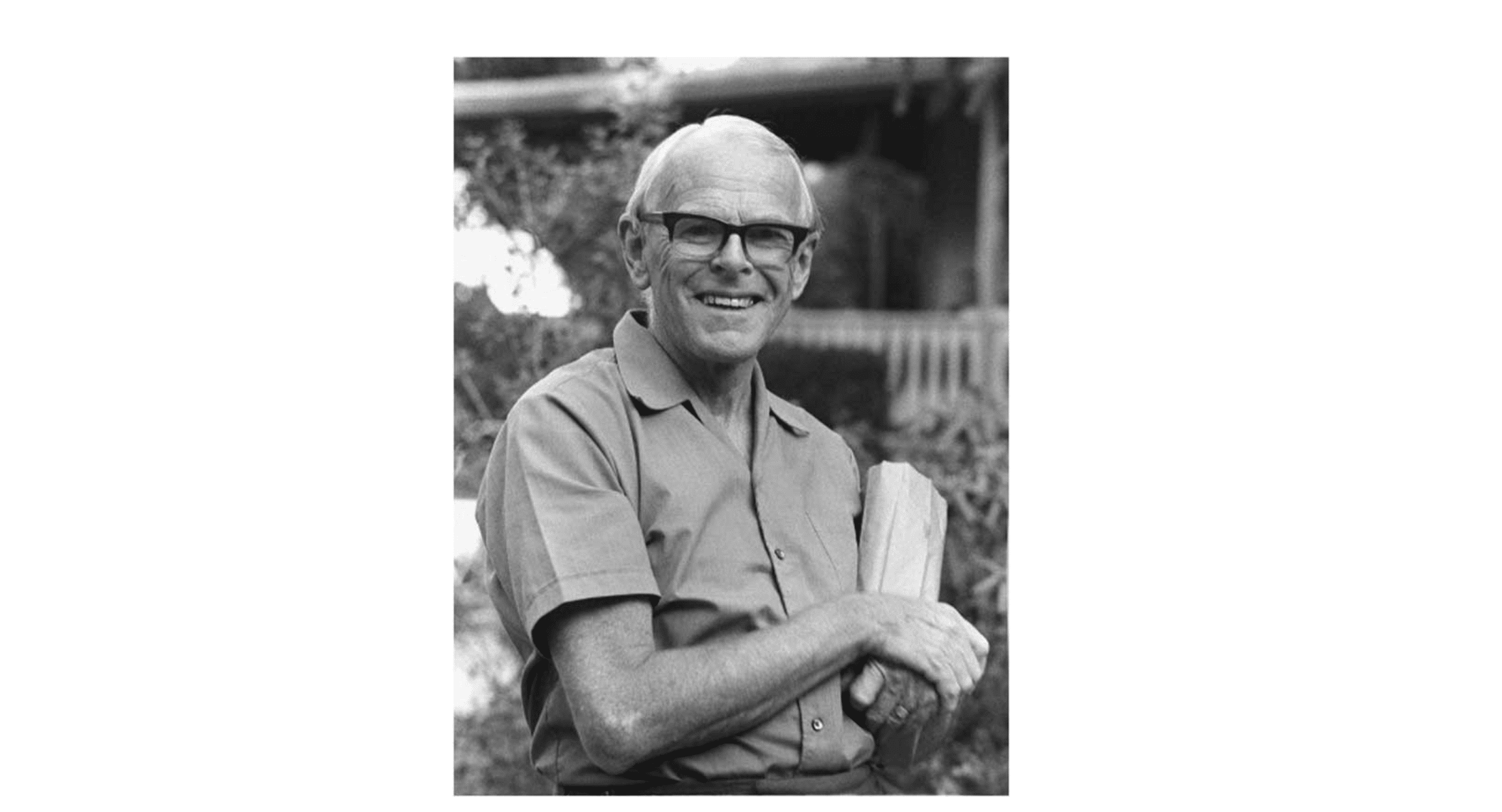

“The Fibre Man by Brian Kellock”: Reproduced by John H. Cummings and Amanda Engineer[1] CC BY

A missionary at heart, Burkitt toured the world giving talks about the importance of fiber in the diet and how to prevent these “non-infective” diseases. (This term evolved into “diseases of civilization,” then “Western diseases,” and now “non-communicable diseases.”) He wrote a book called Don’t Forget Fibre in Your Diet, published in 1979, which became an international best seller, and he became known as “The Fibre Man.” Reading about this phase in his life, I was reminded of Al Gore touring the world with his laptop to warn about climate change, as documented in An Inconvenient Truth. It was at one such presentation that a young Dr. McDougall encountered Burkitt.

McDougall’s encounter with Burkitt’s thinking on diet came in 1971.[5] Burkitt was visiting Michigan to meet with Kellogg’s to try to get them to increase the fiber content of their cereals. While in Grand Rapids, he took the opportunity to give a lunchtime presentation at a hospital in Grand Rapids. McDougall, then a medical student at Michigan State University, was in the audience. What Burkitt shared in that lunchtime talk started McDougall down a new path. In January 2013, McDougall wrote about this encounter:

“Prior to hearing Dr. Burkitt’s revolutionary ideas, I believed that the common chronic diseases I was learning about were all unsolvable mysteries, perhaps due to viral infections or genetic mishaps. After his presentation, I realized, for the first time, that being a doctor might mean more than treating the signs and symptoms of my suffering patients with pills and surgeries. Common diseases could be prevented, possibly cured, by eating simple, inexpensive foods. However, I did not fully understand the practical implications of his lessons until I had made similar firsthand observations as a sugar plantation doctor on the Big Island of Hawaii between 1973 and 1976.”

Burkitt is very quotable. Here are some choice quotes included in Dr. McDougall’s 2013 newsletter about Burkitt:[5]

Burkitt is an important figure in the history of nutrition. He went to Africa on a religiously inspired mission to bring Western medicine to parts of the world that had very little of it in the 1940s. He worked what must have seemed like miracles with children afflicted by the mysterious lymphoma that would be called Burkitt lymphoma. He mended many broken limbs and sewed up many wounds. What he could not have anticipated was how much the local people would teach him about the limitations of Western medicine and the importance of diet. He witnessed how little need they had for Western pills. Their health into old age demonstrated that the diseases of old age he was so familiar with, having trained in the UK, were not inevitable and had much to do with failing to eat a largely plant-based diet rich in fiber.

As the 2018 review authors posit, the approach he used, “in which he created a hypothesis for the cause of a disease based on epidemiological observations, his testing of the hypothesis by experimentation (i.e., transit studies) leading to the proposal of a policy for prevention based on the totality of evidence he gathers, is a model for public health policy today.”[1]

Sadly, with a few honorable exceptions, our society has memory-holed Burkitt’s work and his wholistic view of Western diseases. I find it stunning that all this evidence and theory has been available for over 50 years and was well-known at the time because of Burkitt’s evangelism (my 80-year-old mum, a former home economics teacher with a passion for cooking and nutrition, remembers his work). A clue to the memory-holing may be found in the 2018 review. The concluding paragraph begins, “It is easy to denigrate the fiber hypothesis that postulates a simple cause and remedy for such a wide-ranging and prominent group of diseases now afflicting or emerging in most countries of the world.”

Regardless of whether every detail of his theory is correct, the massive difference in health outcomes between populations eating the Western diet of the 60s and 70s compared to the traditional African diet should have clued Western governments in on the importance of the course correction that Burkitt recommended. Significant changes were needed back then, but the gap has widened even more in the intervening years. The changes needed now are dramatically bigger than they were in Burkitt’s day. Instead of addressing the dietary concerns raised by pioneers like Burkitt, Western governments allowed corporations unbridled access to our appetites and, through unregulated advertising, enabled them to shape popular beliefs about what constitutes good food. The Fibre Man, who died in 1993, surely would have been horrified.

Copyright 2025 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.